There are streets, paths, highways, alleys, dirt tracks and promenades… And there are courses of lives, thirstlands, crossroads and dead ends…

German theatrical release date: October 12th, 2017 - English or German with English subtitles

Film discussions with Heinz Emigholz & Arno Brandlhuber on October 15th (14:30)

and with Heinz Emigholz & guests on October 22nd (15:00) at fsk-Kino Berlin!

- fsk-Kino Berlin: October 14, 15, 21, 22, 28, 29

“Everyone Experiences Space Differently”

An Interview with Heinz Emigholz at the Akademie der Künste by Christoph Terhechte

With the four-part “Streetscapes” series showing at this year’s Forum, director Heinz Emigholz and Forum head Christoph Terhechte met at the Akademie der Künste at Hanseatenweg, one of the key screening venues for Forum and Forum Expanded. They spoke about framing and editing in architecture films, the Akademie building and the necessity of research trips. (Source: arsenal-berlin.de)

In STREETSCAPES [DIALOGUE], you stage a conversation with psychoanalyst Zohar Rubinstein before the backdrop of buildings by Eladio Dieste and various others, with American actor John Erdman in the role of the filmmaker and Argentinian director Jonathan Perel in the role of the psychoanalyst. Was the conversation always intended to form some sort of script?

No. That only emerged over the course of the five-day conversation, which is what’s unusual about the film: it’s during the conversation itself that the director comes up with the idea of making the film we see. It’s there that a temporal inversion takes place. The film depicts a process that’s actually impossible to depict. But I asked Zohar beforehand if there was any reason why I couldn’t record our conversation, as I was worried I might forget something. That obviously goes against standard psychoanalytical practice. As it was clear to him that we weren’t doing any sort of classical psychoanalysis, but rather an intervention or “marathon”, as he called it, he was fine with it.

2+2=22 [THE ALPHABET] by Heinz Emigholz

The conversation between the two of you also revolves around the idea of creative blocks and the strength needed to bring a work to complete. What made you want to get four films off the ground at the same time?

The four films were actually made over the course of three years. I shot 2+2=22 [THE ALPHABET] in October 2013 already, but then I didn’t know where to go with it and put it aside. Talking to Zohar suddenly provided me with the solution as to how the films could be made to fit together. The dialogue with the psychoanalyst is obviously the key to the other films. I edited the dialogue down to the parts that focus on filmmaking. I originally had 260 pages, of which 60 remained at the end. The basic structure is an analysis of filmmaking that then itself becomes a film. My architecture films were often criticised for not including any sort of text, for showing spaces but not explaining anything. This is what now takes place in the third film. In STREETSCAPES [DIALOGUE], the filmmaker recounts what makes sense to him when making films. In this sense, these four films each offer explanations for one another.

You’ve brought your architecture films together under the title of “Photography and beyond”. Why photography and not cinematography?

I do the framing and while I’m preparing the image, Till Beckmann takes care of the technical side of things so that an optimal image is created. I see framing as a photographic act: setting out the frame in full awareness of what you’re still going to film or what you’ve already filmed. That’s a cinematographic decision, but at the same time, I think that each individual image has to be composed in such concentrated fashion that it can stand for itself, rather than just filling in a gap or being included for editing purposes. That’s the same compositional effort also found in photography. Yet the element of time plays a part here too. Duration and editing are always an intervention into how time is constructed, almost like in science fiction.

The approach to framing used in your architecture films has developed into a sort of trademark of yours. Architectural photography is usually much more conservative than your way of grasping spaces photographically.

That came about on the one hand from my features. “Die Wiese der Sachen” and “Der zynische Körper” were already to a large extent devoted to architecture, the only difference being that there were still actors wandering around and saying stuff. But I wanted to get away from such foreground-background relationships, as I felt that the so-called background was just as important as the foreground. When I left out the actors, I could, of course, devote myself far more to spaces. All spaces have a particular language and you have a particular sense of them. You approach such spaces, which also takes place via the soundtrack, of course, and place your body within each one, as it were. The photograph emerges from how I react to this space. I luckily don’t have the same problem as architecture photography, whereby everything has to be encapsulated within three images. I have entire sequences and can thus put much more complicated spaces back together. You call it a trademark, but such films actually never existed before. The first of them were shown at the Forum in 2001. I shot them in the 1990s and thought that it was a crucial idea, yet also a simple one, to enter buildings and show how the rooms unfold within them. I thought that there must already be thousands of films like this, but there weren’t. I don’t want to use that dumb expression “unique selling point”, but what you refer to as trademark just developed from the logic I apply to space. Everyone experiences space differently.

If I may equate you with the protagonist of STREETSCAPES [DIALOGUE], which is, of course, a fiction film, then you describe yourself as a nomad equally capable of being in Berlin or in a hotel room in Montevideo to which you have no real connection. Yet architecture presupposes the very opposite of this. Whether public architecture like the Akademie der Künste where we are right now or residential architecture: buildings are immovable, they seek to create a home.

I sometimes fantasise about what would it be like if I actually lived in the house I’m filming. Sometimes it’s a horrible thought. Architecture takes on so many different tasks. Let’s take Bickels’ kibbutz architecture, for example: I would have loved to live in such a context. But this context hardly exists any more or hasn’t yet re-emerged. What I find interesting about all the many architectures I now have in my head is that I can lie down and say to myself: now I can remember exactly how it was being in one place or another. It’s like taking a holiday in your own mind – thanks to the brain’s odd capacity to conjure up spaces anew. There’s something soothing about that. But I’m interested in a wide range of different constructions, particularly in relationship to film, and not the one dream house built for me. And I’m equally interested in all the myriad tasks linked to construction: social housing, cultural buildings, bridges, engineering structures. I’m interested in bridges but I wouldn’t like to live under one.

Do you sometimes dream of architecture?

Yes, very much so, that’s what my next project is about. It’s about the grammar of dreams, about jumping back and forth in time or inverting it, about the ruptures in how you experience a dream and the impossibility of it ever being repeated. And architecture has always played a big part in my dreams, also constructions of a threatening nature. I also explored that in the discussion with Zohar Rubinstein.

STREETSCAPES [DIALOGUE] von Heinz Emigholz

How do you choose the architects whose buildings you then dedicate your films to? I remember our meeting one time in Buenos Aires, where the Bafici festival was taking place in a former market hall whose concrete architecture fascinated you.

I’d never heard of architect Viktor Sulčič before. After I saw the building, I went to the city archive and looked up everything he’d built in Buenos Aires. Then I went to see it all. That’s how it happens. I don’t follow any sort of textbook entitled “The Most Important Architecture in the World” or such like. I love complicated spaces and some architects are capable of building them and others aren’t. I’m not enamoured of façade artists, but rather building that is constructive. I used to have a list of favourites, which I worked my way through, but then there were always new names being added to the list, like Bickels or Sulčič, who I hadn’t heard of before. I also look at photographs, of course, before I head out on a research trip and I often don’t recognise the buildings from the pictures taken of them, as they’re so heavily distorted by photographic interventions such as wide-angle lenses that I have a totally different feeling of space when I’m actually there. That’s exactly my theme: you have to be there to be able to recognise it. I’ve been going on these trips for decades now, they’ve been extremely important to me. You go there with a small team, there’s no pressure and you have time to properly engage. That was a great period for me. There was so much lying fallow. I’m sick and tired of the self-righteousness of the modern architectural canon because there are so many discoveries waiting to be made that are simply not uncovered. There are too few people engaging with the subject.

Four years ago, Forum Expanded took place at the St. Agnes Church in Kreuzberg, which was built by Berlin architect Werner Düttmann. For three years now, we’ve also been back in the Akademie der Künste in Tiergarten, which Düttmann designed down to the very last detail. What feeling does this place evoke in you?

I’ve known the Akademie since the 1960s, when I came to Berlin for the first time. It was always a place that was extraordinarily strange and attractive for me, both in its proportions and in the way it connects exhibitions spaces with rooms to sit down in and hold discussions. And then there’s the amazing cinema auditorium. I think it was 1974 that I had my first films at the Forum, I wasn’t there myself that year, but rather in the US. When I came back, the Forum still used to take place in the summer and was based here, which was amazing. In 2012, it was also the location for our Think:Film conference with over 300 participants and we noticed in the process how well the building is divided up into rooms which you can withdraw to, rooms where you can hold discussions in smaller groups, and then there’s the large forum and so on. And then of course there’s the fact that the building is located in the middle of this park. It’s strange that the building hasn’t just retained its original charm, but has actually become more charming over the years. Right now there’s so much talk about constructing buildings that are communicative. There was just a competition announced about the 20th century gallery and then you hear that axes were established that run through the building, with a communication point located at its centre. Those are such oddly abstract ideas. Yet all that has already been realised in this building, there was no need to invoke any grand-scale axis philosophy. I also like the building’s form, the strange rectangular block, the quadrangles and also the auditorium with the stage you can perform on from two different sides. The building still exerts the same fascination it did nearly 60 years ago now.

In your film BICKELS [SOCIALISM], you place a greater focus on how the locations are used than in your other architecture films. I could feel your sense of melancholy about something being built for a purpose that no longer exists.

I came across Bickels by accident because I found how the light is constructed in his museum in Ein Harod so unbelievable and was reminded that Renzo Piano adopted the same construction as Bickels for his museum building in Houston, Texas. Bickels was a very educated man, his library is part of the museum in Ein Harod. But his main interest was the special requirements of kibbutzim and cultural buildings. Yet he was also concerned with how buildings relate to one another, public squares, the many theatres that now often lie empty since television has asserted its authority. That interested me more and more: how is the social moment situated within the kibbutz? Culture is extremely important in the kibbutz movement. Bickels showed considerable invention in continually working on new solutions that were then realised in a particular kibbutz. It’s also interesting that he worked with the whole collective on this. It wasn’t about the star architect turning up and just building something, but rather everything was discussed very precisely: what do we need, what can we afford, what dimensions should the building have and what status does it have within our community? That’s a utopian form of construction. It’s the opposite of standard construction, where often nothing more is created than a sculpture for the architect. I despise it when the sculptural is paraded in such a way. That’s why the whole project is called “Streetscapes”, it’s about being out on the street and seeing what catches your eye. No individual buildings are picked out and presented as masterpieces.

BICKELS [SOCIALISM] von Heinz Emigholz

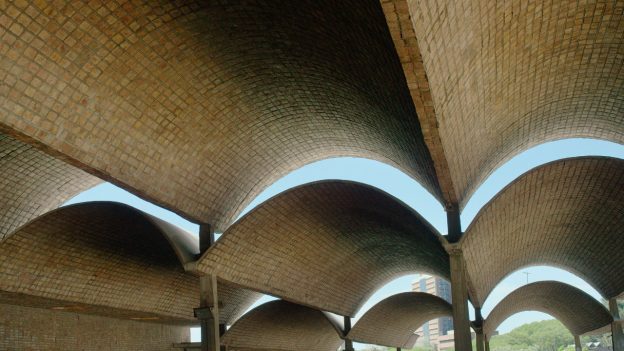

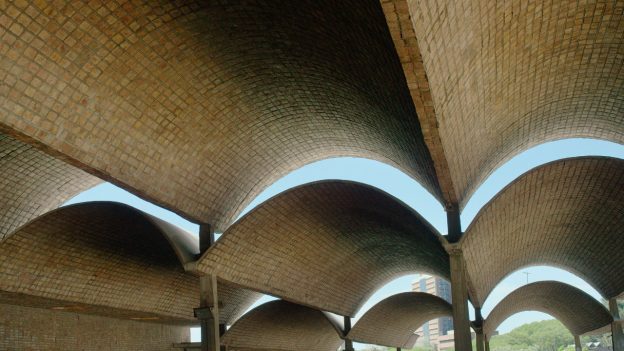

The epilogue of the fourth film DIESTE [URUGUAY] shows the works that this Uruguayan architect realised at the end of his life in Spain. They come across like a mockery of his buildings in Uruguay.

They’re smaller versions of the churches we saw in Uruguay, but in Spain they don’t work. They’re perhaps more photogenic because they’re smaller and more compact, but all that we heard from the people using them in Spain is that they’re useless. They’re too hot in summer and too cold in winter and the congregation prays in the cellar, because upstairs it’s either too hot or too cold. Those were his last years and he was just repeating himself stylistically. But when you see the Iglesia de San Pedro in Durazno, where the brick hexagons are placed within one another and then you see it in Spain with double-paned glass, smaller but also heavier, then you also recognise the history of an architect who stayed true to his formal concept, even if it no longer really worked.

DIESTE [URUGUAY] von Heinz Emigholz